Below the ground of the Euregio Meuse-Rhine!

Below the ground of the Euregio Meuse-Rhine!

1. THE UPPER SIDE OF THE EUREGIO*

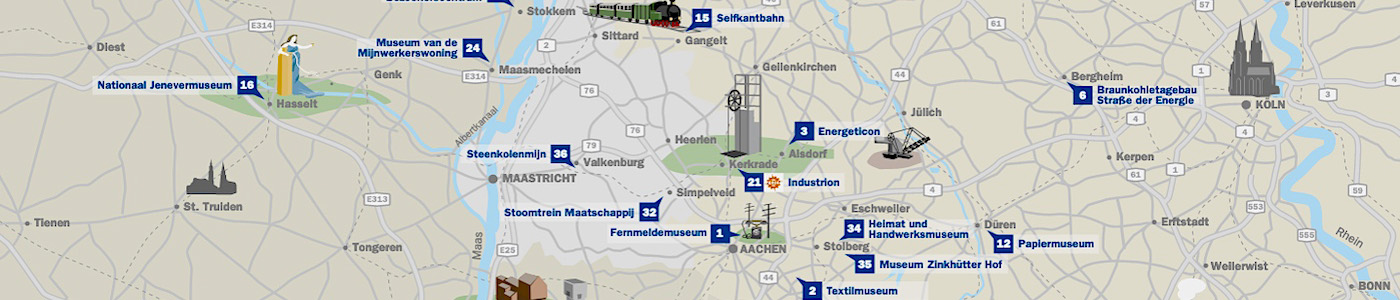

The Euregio Meuse-Rhine comprises the German “Regio Aachen”, Dutch central and southern Limburg and the Belgian provinces of Limburg and Liège. This Euregio is a melting pot of nations, cultures and languages. She is also gifted with a wealth of natural resources, such as flint, chalk and limestone, lead and zinc, lignite and coal, sand and gravel, and even gold-dust. The landscape is surprisingly varied: the plains of the Campine and the Lower Rhine area in the north; the plateaus of the Hesbaye, the Condroz, the chalk district of southern Limburg and the Herve district in the centre, all dissected by deep valleys and gullies; and finally, the northem border of the Ardennes and Eifel in the south, with the unique nature reserve of the Hautes Fagnes (highmoor bogs). The difference in altitude of some 650 m within this relatively small area has caused considerable differences in the climate : an annual temperature of 9.5°C and 700-800 mm precipitation a year in the north form a contrast to the 6.1 oc and 1400 mm rain in the Hautes Fagnes area. Both the relief and the complex composition of the subsurface are the result of a geological evolution during more than five hundred million years. This nutshell highlights some aspects of the subsurface and its geological history (the “lower side of the Euregio”). Of course, the actual landscape (the “upper side of the Euregio”) forms our starting point.

1.1 LAND OF HILLS LAND OF VALES

First of all the Euregio is a land of hills. The numerous toponyms with “berg”/”burg”/”bourg” and “mons”/”mont” (“hill” or “mountain”) illustrate this. Most of them, however, do not refer to real hills or mountains. They are the result of an optical illusion. In reality, the Euregio consists of a large number of flat plains and plateaus, dissected by deep valleys and their corresponding rivers and brooks. We can deduce this from the place names with “dal”/”daal”/”thal” and “val”/”vaux” (“valley” or “vale”).

1.2 LAND OF WATER

The Euregio is indeed a land of water because of the many hundreds of rivers, brooks and brooklets, which cross this country or even originate in this area. Numerous place names are linked to the name of a well-known river or brook (for example Meuse or Maas, Geul, Gulp, Kyll, Geleen, Itter, Inde, Rur or Roer and Vicht). And there are, of course, the many toponyms with “beek”/”bach” (“brook”). With all that water, there must be also bogs and marshlands, such as the renowned Hautes Fagnes with their annual precipitation of 1400 mm. And there are many toponyms with “broek”/”bruch”/”broich” or “meer”/”maar”/”mar”/”moor” (“marsh” or “wetland”) .

1.3 LAND OF WOODS AND HEATH

Woods and heath must have covered practically the entire Euregio a long time ago. We can deduce this from the “heide”/”hé” and “bruyère” (“heath”) toponyms (especially in the Campine, southem Limburg and the Herve plateau) and the place names with “bosch”/”bos”/”busch”/”bois”/”wald”/”fôret” and “lo” (“wood” or “forest”).

1.4 THE EUREGIO MEUSE-RHINE AND THE IMPACT OF MAN

Practically ail the present-day woods in the Euregio have been planted by man. This also holds for the extensive fir and spruce forests in the Ardennes, Eifel and Hautes Fagnes. Preferably, these woods are located on infertile soils or on places which are hardly accessible for cultivation (for example, the escarpment woods along the steep slopes of the river valleys). Since 5000 B.C. farm land was obtained by chopping down and buming the woods on the most fertile soils. The large-scale disafforestation started with the arrivai of the Romans, who rapidly stripped the “green skin” of oak and beech woods from the Euregio. The massive uprooting of woods in the eastern part of the Euregion in the Carolingian period was closely linked to the increased population pressure. This last phase of disafforestation is recorded in the place names with “laar”/”sart”/”rode”/”rade”/”raedt”/”rath”/”roth”/”rooi” (“uprooted”). The more recent toponyms with “haag”/”hagen”/”hage”/”haye”/”faye” (“hedge” or “hedges”) illustrate the transformation and redevelopment of the landscape by man. The process of reafforestation and the arrangement of import crops (for example, cereals, peas, lentils, chestnut and walnut) in lots and fields made that the original “green skin” of the Euregio was gradually replaced by a many-coloured “patchwork blanket”. This completely disturbed environment facilitated the entry of ail kinds of immigrants from central and southem Europe, among them not only rare orchid species, but also the relatively common Foxglove (“Digitalis”).

Of course, agriculture cannot bear the biarne for ail the changes in the landscape. Immediately behind the first farmers came the Neolithic miners, who extracted flint on such a large scale, that this produced small changes in the local environment. ln his “Naturalis Historia” Plinius described the mining of ores at the beginning of our era. The mining of lead and zinc gave rise to the extremely peculiar “zinc flora”, which only flourishes on soils with very high concentrations of heavy metals. The impact of man on the landscape was not restricted to the change of the col our of its “green skin”. The extraction of gravel created a large number of artificial lakes along the Maas between Eijsden and Roermond. Also the relief of the landscape has been thoroughly changed in sorne cases. The Albert Canal has literally split in two the “Pietersberg” hill at the south of Maastricht. Large heaps in the landscape remind us of the now largely abandoned coalmining activity in this region. But the largest man-made difference in altitude can be seen near the highway between Aachen and Monchengladbach, where in 1979 a 200 m high and 5 km wide heap (the “Sophiënhohe”) was created next to a lignite pit (“Hambach”) that will reach a total depth of 470 m. This artificial difference in altitude of 670 m exceeds the natural difference in altitude between Roermond at the northem border of the Euregio and Botrange in the Hautes Fagnes.

2. THE LOWER SIDE OF THE EUREGION HOLES IN THE PATCH WORK BLANKET

The “patchwork blanket”, which covers the Euregio like sorne kind of second skin, consists of heathland, forests and farms, roads, brooks and rivers, villages and cities. We depend on holes in that blanket, if we try to look at its subsurface, the “lower side of the Euregio”. Many of these holes are man-made : open pits for sand and gravel, chalk and limestone, subterranean quarries in the chalk, tunnels and shafts of ore mines and coalmines, excavations for buildings and roads, boreholes for water, and so on. But other holes (or “outcrops”) have a natural origin : the rocks in a valley which withstood the erosion. These holes in the blanket help us to find the connection between the “upper side” (landscape, relief, vegetation) and the “lower side” (the geological composition of the subsurface) of the Euregio. And this, in its tum, allows us to unravel the geological history of this area.

2.1 TERTIARY AND QUATERNARY

The lowlands (below 100 rn altitude) of the Campine, the area with the valleys of Herk and Demer (between Genk and Tongeren), central Limburg (between Sittard and Roermond) and the Lower Rhine area (north of Aachen) possess a cover of Tertiary and Quatemary sediments with a rapidly northward increasing thickness. The deposits consist of sand, gravel and clay with sorne lignite and peat intercalations. These sediments can be studied for example in the lignite pits in the Lower Rhine District. The large and deep pools along the Meuse between Maaseik and Roermond emphasize both the thickness and the economie value of the Pleistocene gravel deposits, which have been excavated here. Pleistocene sand and gravel are also excavated in the Campine. Tertiary deposits outcrop not only in the Lower Rhine District, but also in the valleys of Herk and Demer, and in the northeastem part of southern Limburg around Brunssum. The most important woods occur on the infertile soils of coarse-grained Pleistocene and Upper Tertiary sand and gravel.